Infrastructures of Extremism

Right-wing organisations have gained greater visibility on European streets. During demonstrations, banners often advertise Telegram channels as gateways to extremist communities.

At a rally held in Berlin on 29 November 2025 against so-called “criminal foreigners”, participants promoted channels used for youth recruitment and for coordinating activities at the local level. Understanding how these channels operate is essential to reveal how street-level mobilisation connects to a broader digital ecosystem that fuels the growth of extremism.

These types of Telegram channels collectively form a digital infrastructure that supports the mobilisation of ultranationalist ideologies, enabling the spread of ideology among younger supporters. Across Germany, numerous members of these networks maintain ties to various far-right ultranationalist parties: Die Heimat, which has openly neo-Nazi roots, and Alternative für Deutschland which holds seats in parliament and campaigns strongly against immigration, are just two examples.

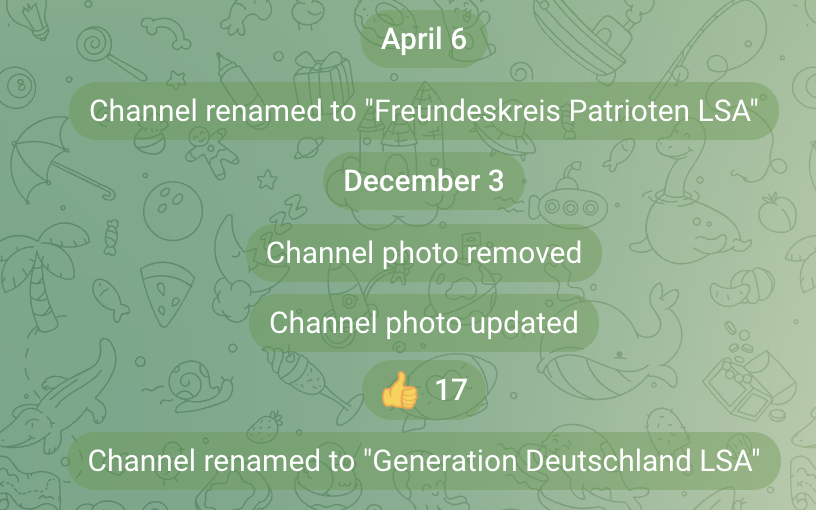

The former youth organisation of the latter party, Junge Alternative, has been classified as extremist and ousted from the public sphere, leading to the recent emergence (29 November 2025) of a successor movement called Generation Deutschland. This new formation has taken on the role of mobilising younger supporters, relying on platforms such as Telegram. Although the national intelligence service has declared Junge Alternative anti-democratic, some local groups that once operated under that banner seem to have simply changed their name to Generation Deutschland and continued their activities as before.

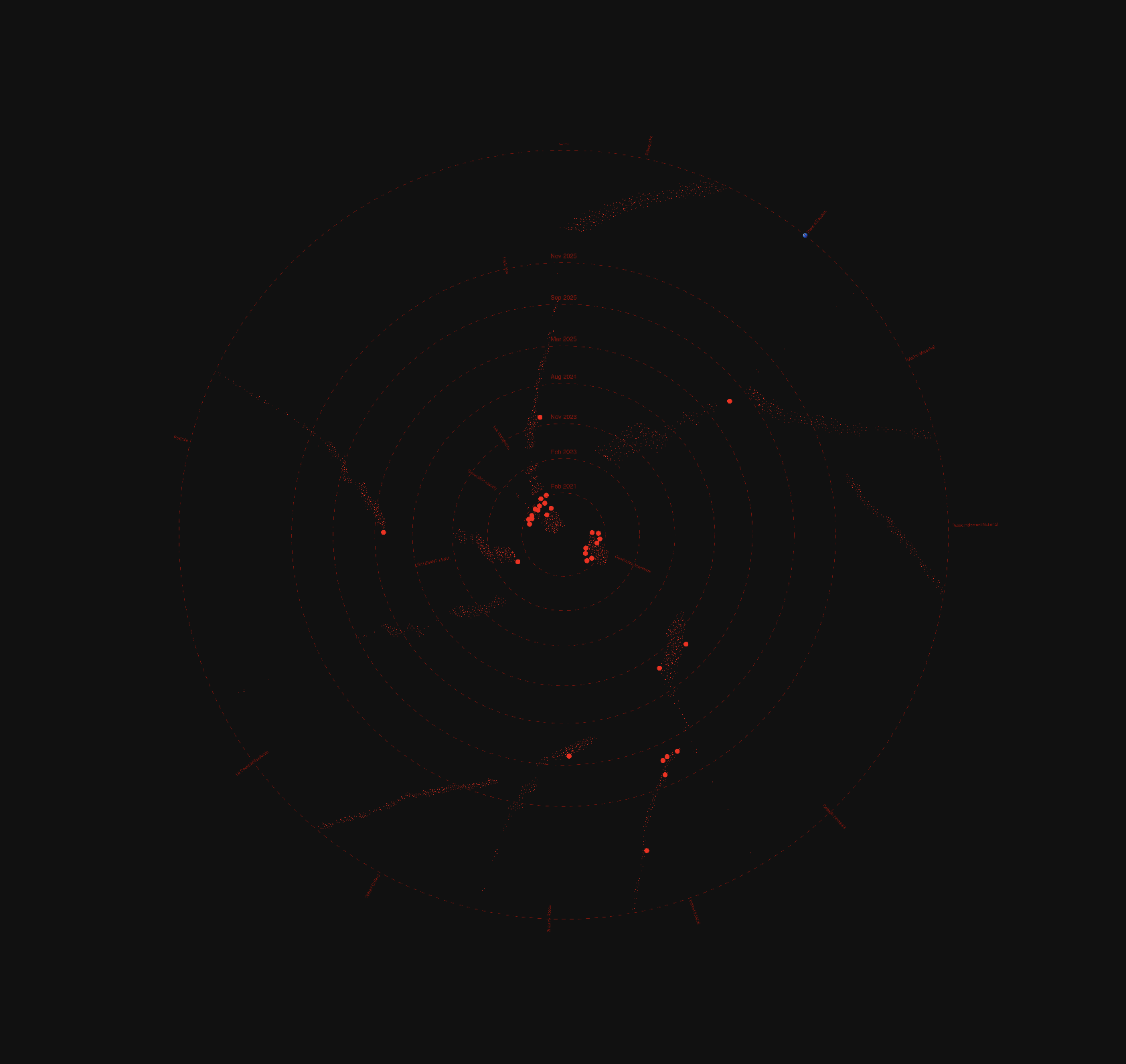

What is becoming increasingly clear is how interconnected these organisations are. Groups such as Generation Deutschland, which seek to present themselves with a more moderate facade, regularly redirect their followers to more radical channels, which in turn refer them to others, creating a continuous chain of racist and ultra-nationalist messages. These links extend far beyond Germany, reaching similar nationalist scenes in countries such as Italy, France, Austria, the Netherlands and Ukraine, sometimes even across the Globe.

Telegram plays a central role in sustaining this ecosystem. It is not simply a place where supporters of a specific group gather, but a tool that keeps these networks in constant communication. Forwarded posts act as pathways from one channel to another, allowing groups to preserve and expand their audience even in the face of bans or restrictions.

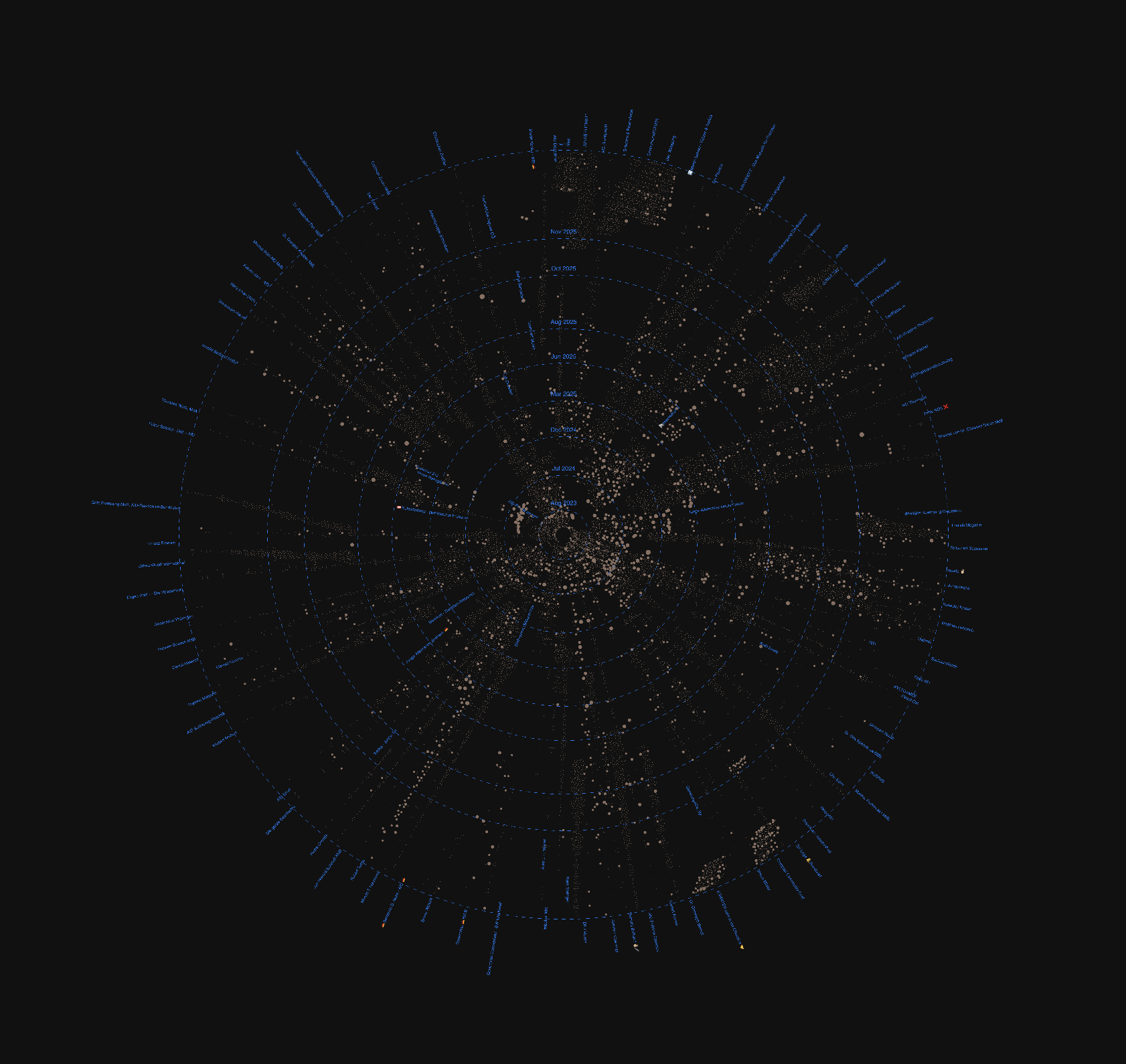

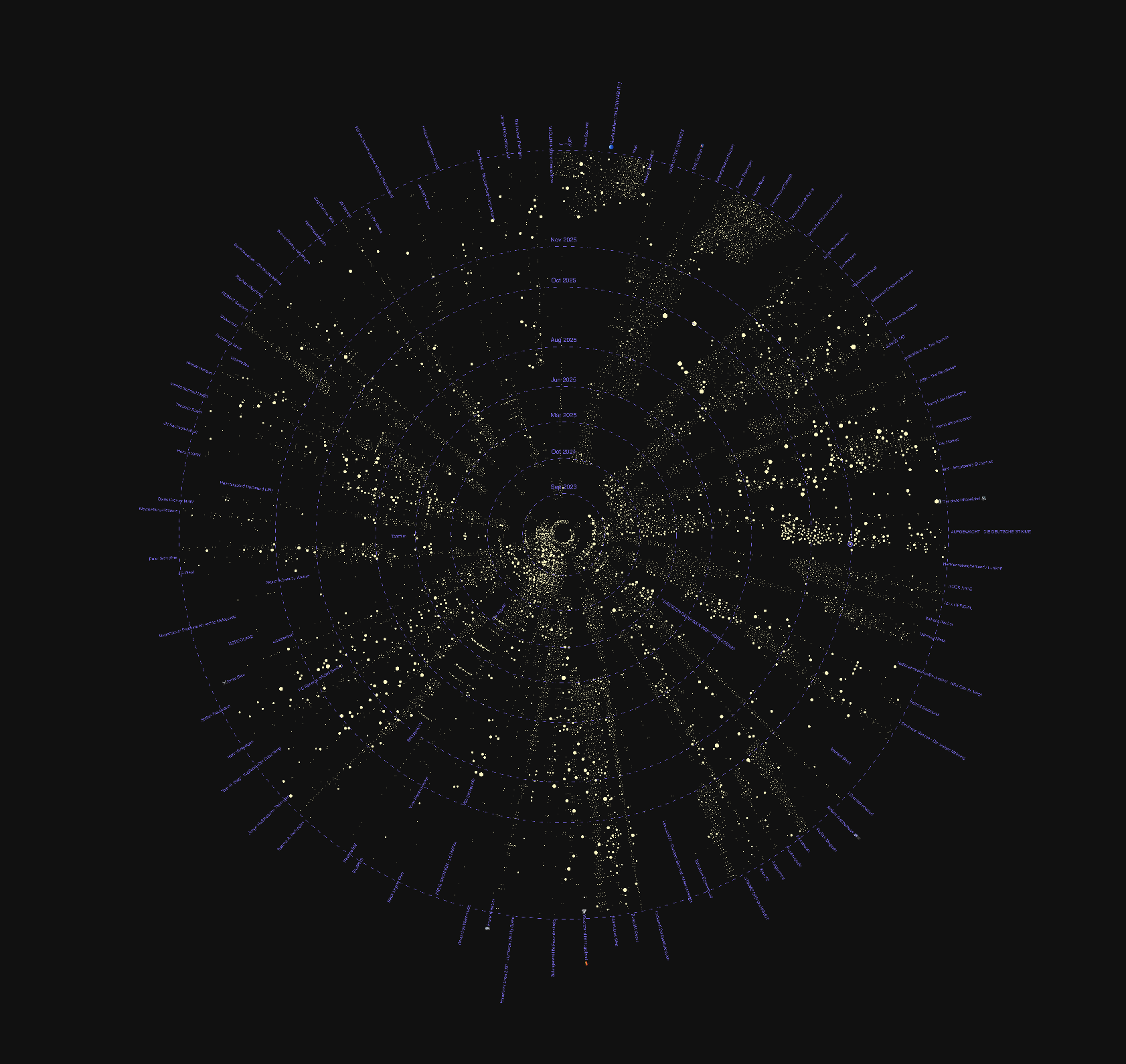

This investigation takes as its input the banners mentioned in the Berlin protest and follows their network as made visible on Telegram. Mentions, forwards, and thematically related messages are collected via automated data scraping and transformed into a series of navigable maps.

This approach shows how individual groups expand and contract, which channels serve as crucial hubs, and how various national factions are connected to one another. Although these maps cannot capture the entire movement (e.g. some of these groups are private, some links we tried to obtain were deleted, probably blocked), they expose part of the infrastructure that allows today's far-right ideologies to circulate uncensored. The lack of moderation on Telegram allows extremists to spread their views, while making their content and relational structures available for monitoring.

Finally, the investigation extends to a wider selection of Telegram groups from different countries. Each, based on the most active channels in that context. Particular importance is given to the most shared content among groups, showing how far-right messages move and adapt across borders.